BY GARY THANDI

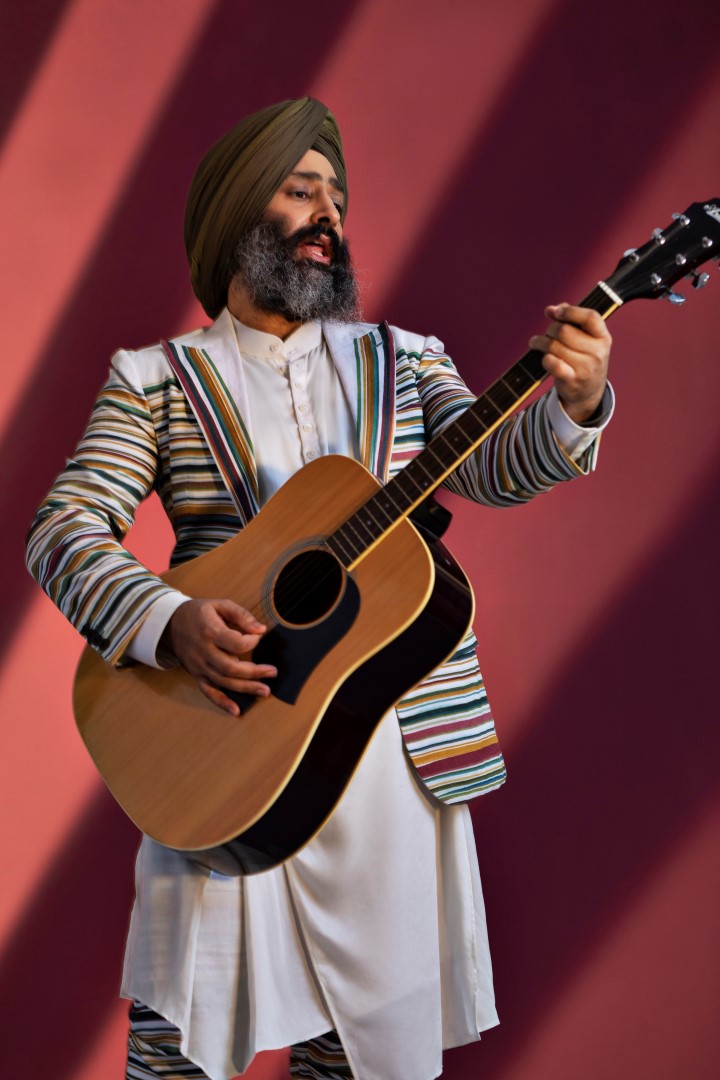

Rabbi Shergill is known for enchanting the crowds with his live concerts, he remains a performer of a kind. He is the heartthrob of music lovers. He burst onto the music scene with his debut album Rabbi in 2004, with one of many standout songs being ‘Bullah Ki Jaana,’ (“I Know Not Who I Am!”) a chart-topper in India and Pakistan. He followed that album up with Avengi Ja Nahin in 2008 and Rabbi III in 2012. His songs have also featured prominently in several film soundtracks – Delhii Heights (2007), Jab Tak Hai Jaan (‘Challa,’ 2012), Romeo Akbar Walter (‘Bulleya,’ 2019) and Happy Hardy and Heer (‘Aadat’, 2020) – and he has appeared on several occasions on MTV Unplugged. Some of Rabbi’s most recognized songs include: ‘Bulla ki Jaana’, ‘Tere Bin’, ‘Chhalla,’ ‘Jugni’, ‘Challa’ and ‘Bulleya’. In 2012, Rabbi launched his own label, Odd One Out Records. His most recent releases include ‘Tun Milen- The Ghost of LSD,’ about the Punjabi poet Lal Singh Dil, ‘Pāṛ Paṛōsaṇi – Thus Spake Namdev’, and in 2019, the acclaimed ‘Raj Singh’ a song about the farmers’ suicides in Punjab.

Born Gurpreet Singh Shergill, April 16, 1972, in Delhi, Rabbi’s father was a gurbani exegete, and his mother principal of Delhi’s Mata Sundari College. His sister, Gaggan Gill, is an acclaimed Hindi poet. His musical influences include major western rock acts such as Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Famers Bruce Springsteen, Led Zeppelin, Blondie, the Ramones and Aerosmith. Rabbi’s music style has frequently been described as an eclectic blend of contemporary, Sufi, rock and roll. Over nearly two decades, his music has been marked by intelligent, thought-provoking lyrics accompanied by creative instrumentalism, fierce independence, and innovation that remains unconcerned with fleeting pop cultural trends.

Various media have described Rabbi as a “Punjabi Sufi-folk musician,” “an eminent name in the music industry,” “an independent musician and urban balladeer,” “The King of Sufi Rock,” “The Sardar with the guitar,” “a pioneer of Delhi’s rock music scene,” “Punjabi music’s true urban balladeer,” “the face of India’s progressive music culture,” an “outsider by choice,” “deeply philosophical” and “a legendary singer-songwriter-guitarist.”

Rabbi shared the following observation about the COVID-19 pandemic with the Indian Link: “One thing it has brought home is the supernormal scale of mass society and the extent of the disconnection and alienation at a human level. A vast gulf exists between the torrent of visuals that guilt-shame us to feel and immerse in the suffering of those hundreds or thousands of kilometers away and our own dried-up hearts–conditioned over a lifetime by asocial individualism–the zeitgeist of our times.”

The visionary artist sat down with DRISTHI Magazine for a Q & A session.

Can you tell DRISTHI Readers a little more about your upbringing?

I was born and raised in Delhi. My mother was a career academic, my father was a scholar and preacher. I went to Guru Harkrishan Public School India Gate, went to Khalsa College for my bachelor’s, and then later pursued my MBA and Master’s Degree in Philosophy. That was my education growing up but I was always interested in music, I always knew I wanted to do something in music.

How did this love for music begin?

We had the Times of India, a newspaper that was then intensely active culturally. They hosted a big concert in which some massive stars from the west–Bruce Springsteen, Tracy Chapman, Peter Gabriel—and other international superstars performed. It was 1988, and I was 16 years old.

Some moments in one’s life can be life-changing. So that was one of those turning points in my life. I went there a normal gawky kid and I came out with a sense of purpose in life. I knew this is what I wanted to do. First, it’s just the music that grabs you, but then you start going a little deeper. For instance, Bruce Springsteen is from this place, Ashbury Park, New Jersey, and it’s not a very prosperous town- – it’s a coal mining town. And he started talking about the problems, the misery, and the little joys of his working-class neighborhood. So, I felt that music doesn’t really have to be glamorous, because I didn’t come from such a background. I lived in North Delhi. We were comfortable, but by no means wealthy. So, I felt that no music reflected our ordinary struggles. And it was by a twist of fate that I understood that there existed people in the West who were talking about unglamorous lives. So that really appealed to me. And the fact that my mother was a poet, my elder sister was a poet, and just that thought provoking things were happening around me.

What are some of the other influences on your music?

I found depth in ordinary conversations in Punjabi, with my grandmother, father, and mother—about life in the village and generally. Those can be very enriching, but somehow the Punjabi music tasked with bring that out can sometimes be shallow.

In Delhi, there was a Western influence, and the cool kids were listening to rock. At school, I was getting all this new music from the west, while at home, I was getting the Punjabi culture from my parents and grandmother. My house almost resembled a library; we had more books than it. I managed to bring all of these influences together in my music. Anything that comes from a genuine, authentic space for me is reasonable. I want Punjabi music to reflect our reality. I want to continue to produce music that is connected to the here and now.

How did you get started in the industry?

My parents gave me some money to get started, and I took that money, went to Singapore and bought a lot of gear, and began to do radio jingles. I had a friend who worked in an advertising agency, and he got me into that work. I then started making small demo tapes of my own music. One of those demos got me my first contract in 1999. From there, I began to work with other artists. And twenty years later, I have 50-60 songs and put out four albums.

Any advice you can give to aspiring artists?

I’d say love something other than yourself. You know, most of the music comes out of very narrow self-love—just love something else. Love is more beautiful, it is more potent when it is shared. And be aware of the fact that whatever you put out in the world is going to come back. A song is a communal experience, we are joined together by this shared language, music, this art.